MUD

WHAT HAPPENED TO AMERICAN POPULISM...

WHAT HAPPENED TO AMERICAN POPULISM...

What had happened to American Populism between 1891, when my great-grandfather ran for office under that banner, and 2016, when Trump did? Or more to the point, what forms of racist exclusion functioned in the earlier agrarian Populist (or “People’s”) party, formed by poor farmers in the South and West in protest against the vast abuses and inequalities of the Gilded Age? What had gone wrong and what was left of their radical critiques of industrial capitalism and fervent expressions of equality?

These questions were political, historical, and deeply personal. I had gone to the library because I needed to trace the inexhaustible threads of invitation and rejection, belonging and barrier, weaving through the ghosts in my family, weaving through our lives now.

Indiana’s Underground Railroad: Routes through Indiana and Michigan in 1848.

from Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, 1898.

In 1850 Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, making it illegal to aid a fugitive from slavery and rewarding all who participated in recapture. That same year, Congress also passed the Swamp Lands Act, designed to encourage the draining and privatizing of wetlands that had been, up until then, public lands “a haven for the powerless and the dispossessed,” including, throughout the South and Midwest, fugitives from slavery. In Indiana, where my ancestors lived, 1850 also brought Article 13, barring all Black people from the state. In the following decades, poor white farmers in Indiana would find less and less cheap land to farm, while their labor would be put to use serving racial capitalism’s goals: draining the state of its non-white populations while converting refuge and shared land into profit for the few.

Mud as transporter of illness, as trans-material, as temporary home for those in motion, as indicator of all that is not yet, has not yet arrived (as capital), not yet been made to produce, could only present a threat to those who sought to stabilize white ownership of land. The swamp was a borderland, haunted by imaginary creatures and real-life exiles. Mistrusted but desired, it presented a potential site of both illness and sustenance, of future wealth and also, of death.

I went to Indiana to feel what I could of the wetlands that remained.

In the Loblolly Marsh, where in the early spring one can lie down in the tall grasses and not get wet, I recorded the sound of the wind and the peepers in the ponds, and I watched some blue shirts billow on a clothesline across the property line. How the law got some bodies moving and other bodies killed, how the law made property for some out of land that had once protected those who were property or had none, and how the map I carried in my phone marked the paths of capital’s flow but not the pathways used for flight: these things did and did not sound through the recordings that I made.

photos by Christopher Kondrich

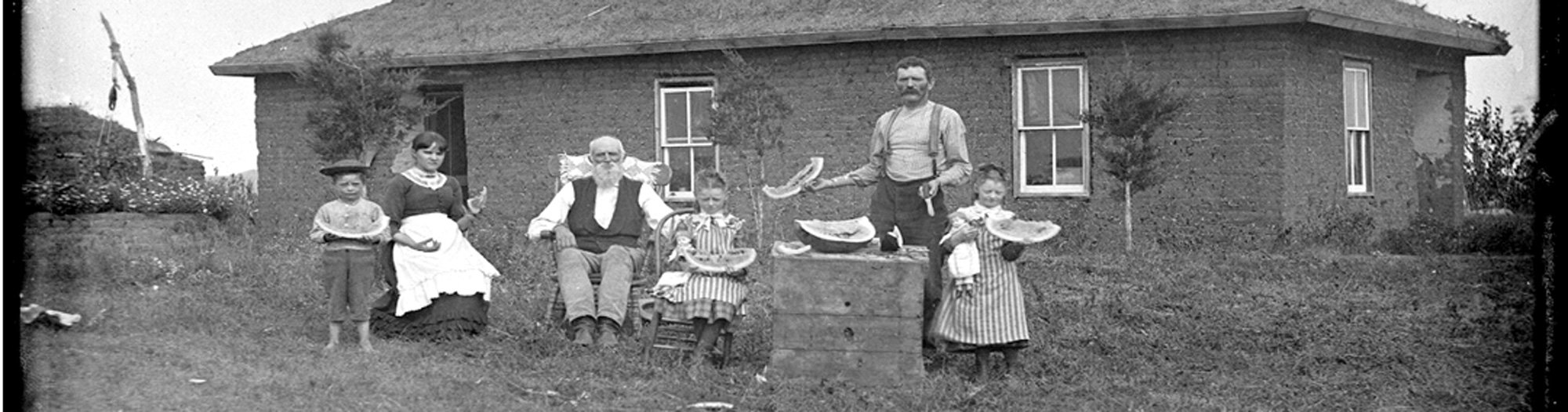

In 1881, at the age of twenty-six, Kem boarded a train headed for Nebraska. There he received, as remedy for his poverty, 320 acres of grasslands that he would again fail to farm. Just as the history of wetlands remains as residue in Indiana’s current social, economic, and ecological life, the residue of mud—a commons, a shelter, and finally a site of impossible and exploited labor—clung to Kem’s life even as he tried to leave it behind. For while the Homestead Act—like the Swamp Lands Act and the Indian Removal Act before that—encouraged people considered white to become property owners on land previously held in common by people who were not, and thereby lifted up some of the nation’s poor laborers, it nonetheless left many of its recipients no better off than they’d been.

And yet ten years after Kem arrives in Nebraska, he will find himself a founding member of the new Populist Party and then, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives where he will attempt to alter the laws that he had been oppressed by. The free mobility of whiteness is a product of and producer of the law.

The Independent People’s Party (Populist) Convention at Columbus, Nebraska,

where Omer Kem was nominated for Congress. July 15, 1890

We begin with a body—a legislative body, a national body, a body in a House. Like all bodies, this body has boundaries, skin. It also has holes, just as the house has doors and windows. And just as doors and windows can be broken, the body itself is vulnerable; it is, after all, alive. There is illness, pain, incapacity, rupture, or simply, there is more. Law’s job, law’s science, is to mark and underscore the boundaries around this body—to repair where there is fissure, to remove excess, to sew the body shut again.

Inside the House’s chambers, the law’s tools, the law’s method, is language, while on the streets, the law’s tools are batons, tasers, guns, and cuffs. The law as boundary “cannot help but be armed. . . . To those who transgress it, it replies . . . with absolute menace.” All vigilant efforts to protect a body from invasion will tend toward violence, one way or another. In other words, language has a violence of its own.